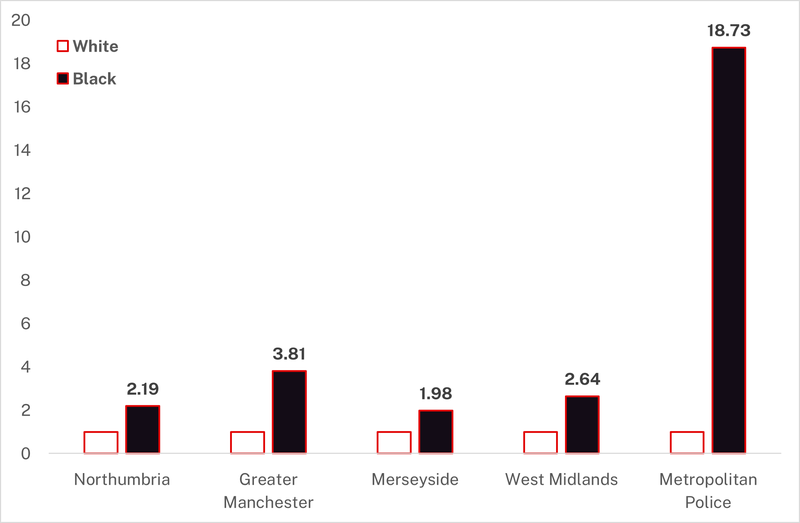

Exclusive | Met police search Black Londoners 18 times more than white people under section 60

It is the third consecutive year of increases in section 60 searches. Nothing was found in 89% of searches under the power

Black Londoners were searched 18 times more than white people under section 60 in the past year, according to analysis shared with Black Current News.

Home Office data shows that suspicionless stop and searches have risen for the third year in a row, with section 60 searches increasing from 5,288 to 5,572.

Nothing was found in 89% of these searches.

Section 60 allows police to stop and search people without reasonable grounds in a designated area for a limited period, usually after incidents of serious violence or when officers believe violence may occur.

The Met drove much of the rise and the disparity, with the gap between Black and white Londoners searched under section 60 widening from six times in 2023/24 to 18 times in 2024/25.

Officers carried out 504 section 60 searches of Black people in 2024/25, compared with 107 searches of white people.

Once population size is taken into account, this results in Black Londoners being searched 18 times more often than white Londoners under the power.

A spokesperson for Stopwatch, the policy group that examined this data, told Black Current News: “The widening ethnic disparity in stop-searches represents a deliberate targeting of Black people by the nation’s biggest police force, using a version of the tactic that allows officers to circumvent having to justify their activity on reasonable grounds.”

“The political obsession with the supremacy of law enforcement over civil liberties has also led to a situation where the comfort of officers exercising their power rides roughshod over the rights of ethnic minorities, so much so that police are unable or unwilling to carry out their statutory duty when recording the ethnicity of individuals searched.

“Met chief Sir Mark Rowley has made a great play of how section 60 searches in particular can save the lives of young Black people, but the figures demonstrate a worryingly large gap in reliable information on the ethnicity of people searched under that power.”

The spokesperson added: “How can Black people trust the Met to make any progress on tackling racism if they do not know the ethnicities of half the people they search, under a power that is inherently less transparent than the standard search?

“The Met’s so-called anti-racist reforms, such as their stop and search charter, mean nothing if this contradiction is not resolved.”

Additional Home Office figures show how the gap emerged.

Officers carried out half as many searches of white people under section 60 as the previous year (223 down to 107) while searches of Black people rose by 40 per cent (356 up to 504).

The Met’s data is further affected by officers’ failure to record ethnicity.

Ethnicity was listed as ‘Not Stated’ in 36,824 section 1 searches, 30% of the total, and in 686 section 60 searches which is 48 per cent of all such searches carried out by Met officers. Both figures sit far above the national average.

‘Section 1’ is the standard stop and search power that allows officers to search people when they have reasonable grounds to suspect they will find stolen or prohibited items.

When approached for comment, a Met Police spokesperson said: “We recognise that the statistics on Section 60 stop and search highlight a racial disparity in London, and we take this seriously.

“Different crimes impact communities in different ways, and tragically, knife crime continues to disproportionately affect boys and men, particularly those of African-Caribbean heritage, as victims.

“Our priority is to protect lives, and stop and search remains one of the tools that can help prevent harm and remove weapons from our streets.”

Campaigners say the lack of recorded ethnicity in nearly half of the Met’s section 60 searches suggests the racial disparities may be even higher than reported.

This follows revelations that race discrimination employment tribunal claims by Metropolitan police officers and staff more than doubled in the last financial year, raising further questions about systemic problems within the force.