This article forms part of Black Current News’ ongoing commitment to preserving the stories that are too often sidelined or forgotten.

I travelled from London to Wolverhampton on a crisp autumn afternoon to meet Mrs Esther McCurbin. We sat in the Wolverhampton Wellbeing Hub, a community space where Caribbean elders often gather to talk, remember and pass time.

The interview took place in a recreated Caribbean front room which is very cool. A room built with the textures and touches of early Windrush generations of the 1950s and 60s. Patterned wallpaper, religious prints, ornaments, old radios, the infamous paraffin heater, crocheted cloths, trinkets and more. It felt familiar, warm and heavy with memory.

To be honest, Ms Esther was initially reluctant to speak with me. Though the interview was pre-planned, she hesitated. Years of repeating her son’s story, of calling for justice with little response, had understandably left her weary and disillusioned.

Before recording, we spent a long time talking through her concerns. About trust and fatigue, about the emotional cost of speaking when the system appears unmoved. We bonded over a shared frustration at the plight of our people.

I spoke about other deaths in custody I have covered over the years, cases that echo her son’s in unsettling ways, and explained that many people, myself included, were born after Clinton’s death and did not grow up hearing his name. This, I said, was an opportunity to place him back into public memory.

The interview that followed was conducted on the record.

Christmas has just passed, at this point.

Across the UK, families gathered to eat, laugh and exchange gifts. However, for Ms Esther, festive periods offer little comfort. They sharpen a resounding sense of absence.

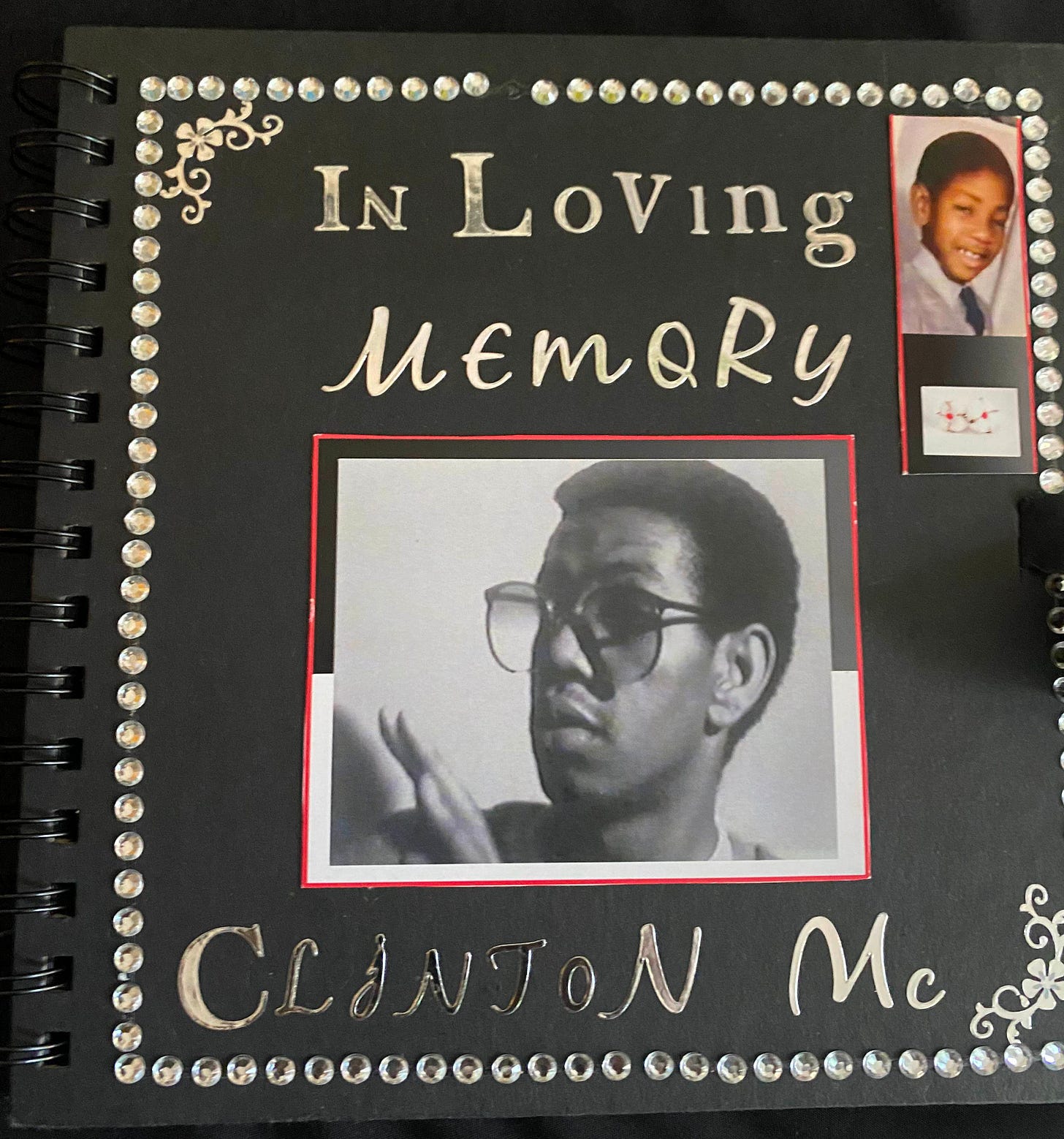

She is grieving her son, Clinton McCurbin, who died in police custody in Wolverhampton in 1987.

Certain dates hit harder than others. Birthdays bring the grief back in full.

“I didn’t have any energy. I didn’t feel good. I didn’t want to leave the house,” the 81-year-old says of her son’s birthday.

“Sometimes I don’t want to get out of bed or eat”.

Clinton was her first child. He was just 24 years old when he died during an arrest by West Midlands Police officers in Wolverhampton on 20 February 1987.

Officers were called to a Next store in Wolverhampton town centre after a shop assistant suspected Clinton was using a stolen bank card while making a purchase - an allegation that was never substantiated.

Civilian eyewitnesses later told the inquest that restraint was applied around Clinton’s neck before he died from asphyxia.

The circumstances have since drawn comparisons with the killing of George Floyd in the United States more than three decades later, which sparked global anti-racism protests in 2020.

Nearly four decades later, Clinton’s mother is still waiting for answers. His death was ruled a “misadventure”, there has been no apology from West Midlands Police and no officer has ever been convicted.

“He was quiet”

Before Clinton became a name associated with protest and injustice, he was simply a son.

“Clinton was my first child,” Ms Esther says. “He was quiet…more withdrawn than the rest”.

She describes a young man who kept to himself, joined the Scouts, did his chores and gave her little cause for concern.

“I never have a complaint from school,” she says. “Not Clinton, never. His teachers, the headmasters, they all take on to Clinton.”

After leaving school, Clinton trained in electrical welding. Work was sporadic. He spent time in London with relatives before returning to Wolverhampton to find work. Not long after, his life was cut short.

The phone call

Ms Esther remembers the moment she learned her son had been killed.

“It was a Friday evening after work,” the grieving mum recalls, explaining that she’d just returned home from shopping when the phone rang.

It was Michael, her other son, who said: “Mum, they killed Clinton”.

She says the phone dropped. For several minutes, she remembers very little.

In the days that followed, Ms Esther travelled from London to Wolverhampton with her sister.

When she arrived at the funeral home, she did not see her son. Her sister and son went in to view him instead.

“They wouldn’t let me see Clinton,” she says.

The decision, she explains, was made out of concern for her wellbeing. She had lost her own mother around the same time and her family feared the impact of what she might witness.

Clinton’s funeral was held with a closed casket.

“I was in a lot of pain,” she says. “A lot of pain.”

Protests and policing

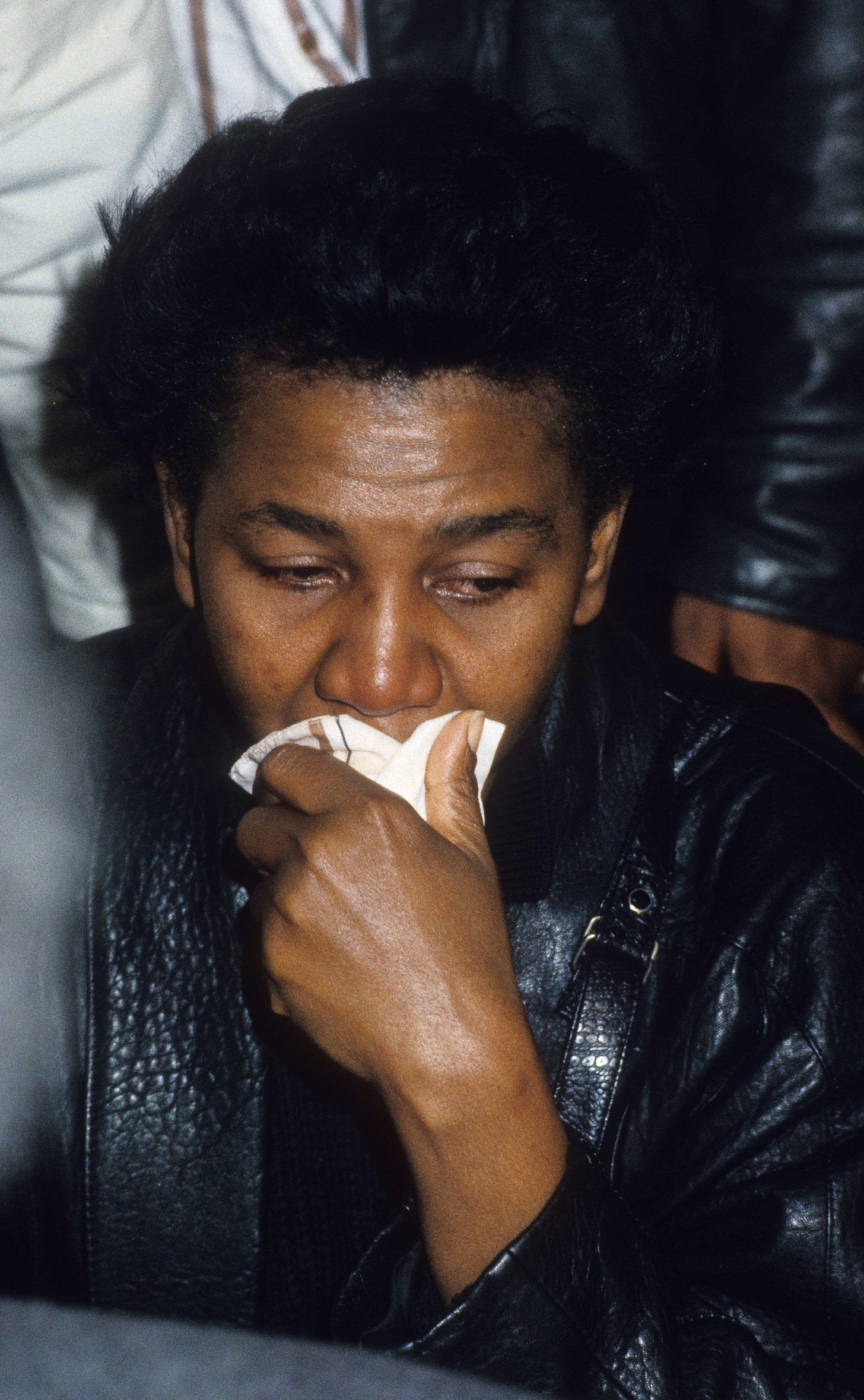

Clinton’s death sparked protests in Wolverhampton, with the main demonstration taking place on 7 March 1987.

Hundreds of people from across the country travelled to the city, amid widespread warnings of unrest.

Express and Star, the local newspaper, ran a front-page story predicting violence, shops along the proposed route were boarded up and faith leaders urged their congregations to stay away.

Heavy snowfall on the day reduced numbers, but those who did attend marched through a largely closed city under a heavy police presence, demanding justice for Clinton.

On the day of his funeral, police were again present, claiming they were there to prevent disorder.

“They said they come to prevent riot,” Ms Esther recalls, explaining that community members challenged that explanation.

“If there’s any protection (were needed), it’s protection from them, not from our own people,” she says.

The scale of grief and tension that day was overwhelming. Ms Esther fainted and missed parts of the funeral service.

“I was out of it,” the elderly mother says, adding that her own mum had recently died at the time.

Clinton was buried in the churchyard.

‘Death by misadventure’

An inquest into Clinton’s death opened in October 1988 and concluded with a jury verdict of ‘death by misadventure’ on November 1, 1988, at Wolverhampton Coroner’s Court.

Ms Esther attended proceedings but says she struggled to understand what was happening. Looking back, she believes her family was poorly represented.

“There was no evidence of a stolen credit card,” she says. “The card was his”.

She recalls being told the amount in question was around £70, though she says details were never clearly explained to the family.

Medical evidence from two pathologists agreed that Clinton died from asphyxia caused by compression of the neck, according to court documents seen by Black Current News.

Civilian witnesses told the inquest that an officer’s arm was around Clinton’s neck during the struggle.

One witness reported hearing an officer say, “Hold his neck - I’ll break his bloody neck,” a claim the officer disputed.

Clinton’s family later challenged the inquest verdict in the High Court and Court of Appeal, arguing the jury had been misdirected.

Both courts refused to overturn the finding of misadventure.

At the time, Paul Boateng, a prominent lawyer and Labour MP, supported the McCurbin family in their fight for justice and attended the inquest.

“The inquest said it was death by misadventure,” Ms Esther says. “Justice has never been served. His death was like nothing…like a dog on the street side”.

Faith, survival and purpose

What has sustained her over the years is faith and church.

“I depend upon God,” she says. “So I don’t get too overwhelmed, too sick, too worried.”

She agreed to speak now because she wants Clinton’s story to travel beyond her own family and local community.

Ms Esther’s hope is that telling the truth might even prevent other families enduring the same pain.

“We are just people,” she says. “Black, white…it doesn’t matter”.

Even now, she thinks about the generations coming after her.

“It’s important his nephew and his grand-nephew feel justified,” she says. “That they know their uncle and great-uncle got justice.”

Nearly four decades after Clinton’s death, racial disparities in policing remain a live issue in the West Midlands.

West Midlands Police data from mid-2025 shows that Black people, particularly young Black men, continue to be disproportionately subjected to police use of force across the region.

While most encounters do not result in serious injury, campaigners argue that the data reflects a long-standing pattern of heightened surveillance and physical intervention in Black communities, raising ongoing questions about accountability, restraint and the use of force.

A former West Midlands Police chief inspector recently warned that racist officers from the force are “on duty every day”.

Launched this year, the Clinton McCurbin Memorial Campaign is calling for a blue plaque at the site of the former Next store in Wolverhampton, alongside a programme of remembrance, education and public engagement.

Spearheaded by Ms Esther alongside campaigners Patrick Vernon and Ruth South, the initiative also aims to also create a digital archive preserving Clinton’s story as part of Black British history.

For Ms Esther, remembrance is inseparable from accountability.

“I’m not asking for money,” she says. “I just ask that Clinton’s name be cleared - that’s all. That’s justice”.

“Even if it’s after I’m gone. It’s okay.”

This post is public - please feel free to share it.

Got news, a tip, a story idea or thoughts on our coverage? Email admin@blackcurrentnews.co.uk. We read everything and take our community seriously.